This post originally appeared in TechCrunch.

Warby Parker is astonishingly successful, whether you judge it by the rave reviews of customers, its valuation or, more impressively, by the number of startups that compare themselves to the iconic eyeglass innovator. Over the last couple of years, I’ve met with dozens of entrepreneurs who have pitched themselves as the “Warby of ________.”

Disrupting any category is difficult, but the consumer goods space can be one of the hardest, given the entrenched competitors, myriad channels and the need to appeal to ever-changing consumer tastes and trends. In the past, VCs rarely ventured into areas that seemed more like consumer packaged goods (CPG) than pure technology, but these lines have blurred. Some of the biggest successes here in the NYC tech scene sell glasses (Warby), mattresses (Casper) and razors (Harry’s/Dollar Shave Club).

Many of the “Warby of X” startups are attractive. The products are generally well designed. Their marketing strategies seem plausible. But so far, we haven’t invested in any. I fear that many of the more recent consumer product-oriented startups put too much stock in their ability to build a brand, or — even worse — their ability to hire an agency to build the brand for them. Strong marketing is certainly necessary, but not sufficient for building venture-scale businesses. These companies have all found something more significant, usually the industry structure itself, to exploit to their advantage.

When discussing these companies, people too often focus on the design and not enough on the deep understanding of the market structures they exploit. Slick messaging and innovative industrial design capture consumer attention, but it’s the founder’s focus on outsize profit margins that captures VC interest.

Warby Parker: Wedging Into A Vertical Market

Eye care in the U.S., and most of the world, is dominated by a Italian company called Luxottica. You’ve probably never heard of them, but they control 80 percent of the market for eyeglasses. They’ve locked up licensing deals with Oakley, Prada, Dolce & Gabbana and basically every other high-end brand to design fashionable specs. They manufacture their own glasses and have purchased or partnered with the best category retailers, including LensCrafters, Pearle Vision and Sunglass Hutto dominate distribution. They even provide optical insurance!

Like Apple, Luxottica has vertically integrated to such a degree that it’s very difficult for anyone else to compete. Luxottica has a near monopoly on eye care, and their scale makes it difficult for anyone to wedge their way into the value chain. Anyone who wants to compete needs the will, capital and connections to recreate the entire supply chain. This strategy has performed beautifully. Luxottica earned revenues of $7.6 billion in 2014 and took 68 percent in gross margin.

The eye-care market is especially difficult to crack because of the necessity of prescriptions. In the past, eyeglasses were generally purchased at the site of one’s eye doctor. Moving a prescription was cumbersome, and these eye docs often made it difficult to transfer it. No wonder the waiting rooms of many docs were filled with frames — in essence, they were running a retail practice coupled with a medical office. Because Luxottica owns many of these storefronts, they’re able to capture margin at every step of the process.

People too often focus on the design and not enough on the deep understanding of the market structures they exploit.

What Warby was able to capitalize on was the increasing ease and comfort modern consumers expect when shopping. Warby has innovated the ordering process — with online and offline try-ons, 60-80 percent cost reductions and easy returns, they were able remove the friction of buying specs online. Warbycould undercut Luxottica on cost and offer a unique aesthetic, while still retaining healthy margins.

This isn’t the case in most markets, and it isn’t easy. Warby had to go “full stack” from Day One, building, branding and shipping their glasses, but it earned Warbya healthy valuation for its efforts. Nonetheless, these important, yet idiosyncratic aspects of the eyewear industry don’t neatly cut and paste into other categories.

Casper: Innovation In Logistics

Eyeglasses and mattresses seem to be completely different product categories, but the market dynamics are very similar. The $9 billion U.S. mattress market is essentially controlled by two private equity firms who bought up the most valuable brands in the market. The companies that ran these businesses cost-engineered the products to make them cheaper to produce, for instance, by making mattresses singled-sided — which forces more frequent replacements. Mattresses are big and bulky, and rely on specialty retail locations staffed by salespeople that make used-car salesman look honest. Still, limiting competition and channels meant margins were protected. Until Casper came along.

Casper cuts through this knot by shipping a full-sized mattress in a conventional box via UPS or courier. Its memory foam design and innovations in packaging allow the mattress to be shipped without the typical hassle of scheduling a delivery, having moving guys traipse through your home and plop a mattress in your bedroom. The mattress is heavily compressed and packaged such that it expands when opened and serves as a compelling brand touchpoint — just watch one of the thousands of unboxing videos on YouTube — it’s worth it!

Casper has been able to create a differentiated product at a low cost, figure out a better way to sell and deliver, all while keeping margin along the way.

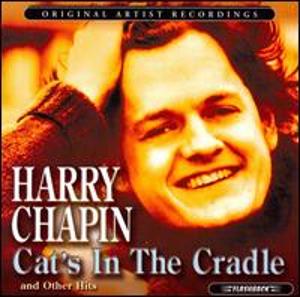

Harry’s: Owning Production Cuts Out Middleman

Like the market for glasses and mattresses, the $3 billion U.S. razor market is huge and concentrated, with Gillette and Schick accounting for 70-90 percent of sales. However, the razor business uses a completely different playbook than the one established by the mattress barons.

The two leading razor makers invest a small fortune in R&D, figuring out how to put more blades on every flat surface on the razor, adding battery-powered features and “track balls” to create the perfect “shave.” They then protected these innovations, as well as the simpler ones that actually make their razors useful, with patents — which cause prices to spiral upwards. Razors have never been better, but that fanaticism for follicle removal comes with an obscene price tag.

Enter Harry’s and Dollar Shave Club. Both companies found razors that were “good enough,” secured manufacturing relationships and built brands around them. They stripped all the extraneous stuff, sought a direct-to-consumer relationship and have captured significant market share as a result.

Most innovative companies would shy away from competing with the likes of P&G or Schick. Not Harry’s. Instead, they purchased a world-class blade production factory in Germany. They realized that while they could disrupt the $5+ retail cost of competitive blades, they needed a high-quality product. People (and their skin) are sensitive when it comes to shaving. Additionally, I suspect Harry’s has to work carefully to avoid infringing on patents, but their success of late has certainly given the big guys a bit of a market-share haircut while earning sharp valuations.

“This For That” Isn’t Enough

All three of these businesses are characterized by a small number of competitors, structural impediments to market entry and consequently high margins. Not every business shares these dynamics. The fashion market is well served, and margins are compressed at most price points. Consumer products, without benefit of a unique and defensible IP, have a difficult time in the market. Basically, if a product can be sold on Amazon, you can be sure the margin will asymptote toward zero.

In many cases, venture capital probably is the wrong funding tool — something like Kickstarter is a better fit.

If you’re going to pitch a VC a business in the mold of Warby or Casper or Harry’s, do the work to make sure you’ll enjoy similar kinds of structural advantages. Ioften ask entrepreneurs what’s unique about their industry — not how is it similar to eyeglasses or mattresses but, rather, how it’s different. Founders should bathe themselves in the nuance of an industry by attending trade shows and talking to insiders.

If you don’t have these advantages, you might get early funding, but you will have a much harder time earning the valuations those companies have enjoyed. In many cases, venture capital probably is the wrong funding tool — something like Kickstarter is a better fit.

The Gap Between Successful Startup And “Also-Ran” Is Razor Thin

It’s not surprising that investors and entrepreneurs have taken notice of their success. VCs and founders can act a bit like lemmings. The key thing to remember is that each of these businesses has unique characteristics, and simply picking a long-ignored category and following the playbook created by these startups is by no means a recipe for success — or funding.

This isn’t to say startups in more competitive markets with thinner margins can’t take lessons from Warby Parker, Casper or Harry’s. In addition to picking great markets, the teams behind them have put on a master class when it comes to building brands and executing their businesses. Mattresses were comfy or cost-effective before Casper, but they were never cool.

These companies have demonstrated that you can build a healthy business on the back of high net promoter scores and by leveraging emerging marketing channels like podcasts and YouTube. Still, it’s just really hard to build a venture-scale business in most markets absent a structural misalignment.

I’m not saying we’d never back a CPG-focused startup, but we’ll need to see founders who understand the razor-thin difference between successful startups and also-rans.